AMBALANGODA, Sri Lanka -- In Ambalangoda, a vibrant Sri Lankan coastal town of fishermen, sunshine and traditional mask makers, two unique and ancient art forms are battling for survival. One, known as rukada, uses almost life-size puppets to thrill and amuse audiences.

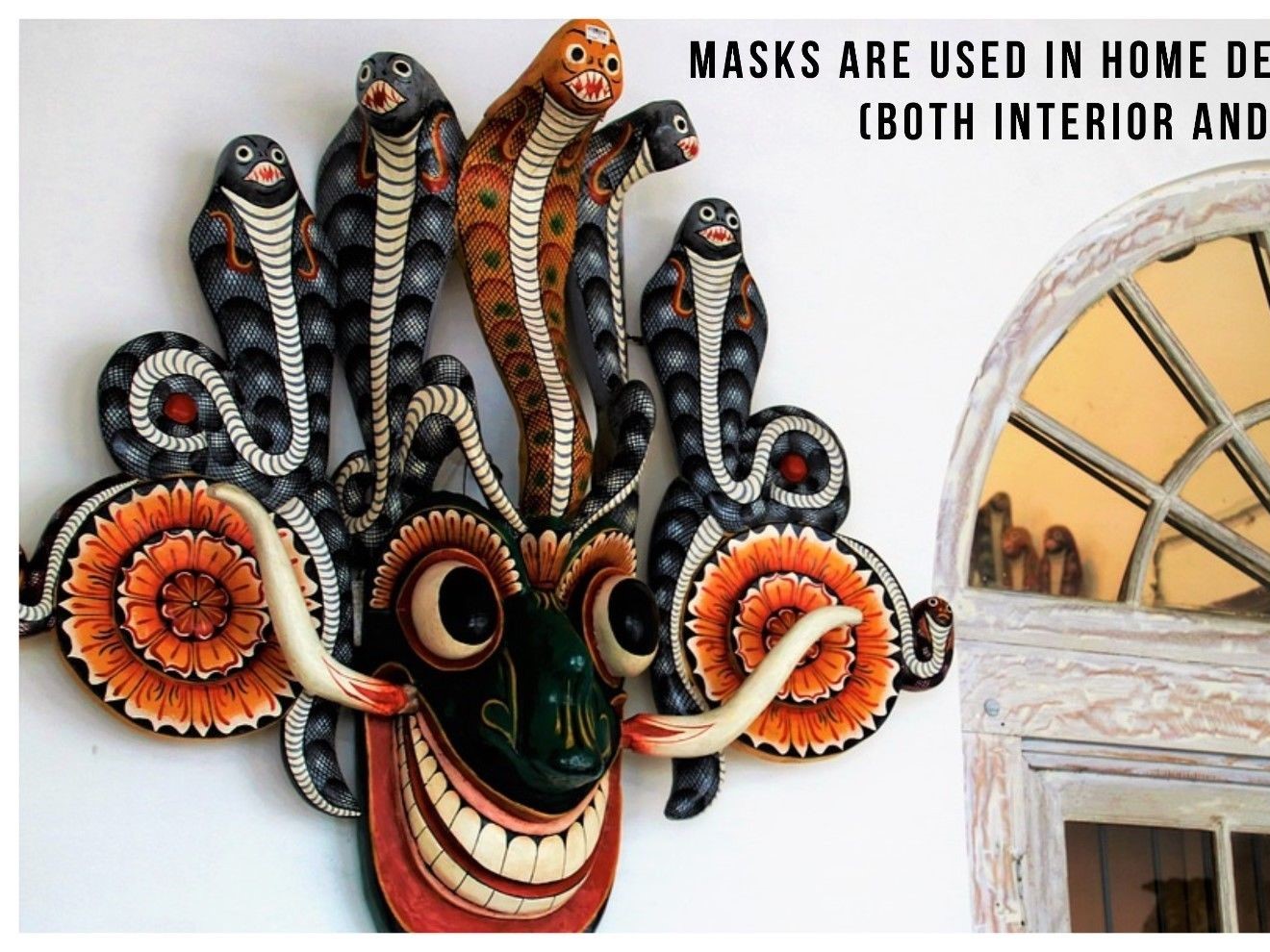

Its not-so-distant cousin is the art of masked drama called kolam, which translates best as "farce." In kolam, costumed men wearing masks act out ancient stories, often to raucous effect. What unites these two art forms are the traditional masks made in Ambalangoda and other maritime towns of Sri Lanka's south, such as Balapitiya.

Both traditions deal with material from Buddhist lore -- the Jathaka tales, which are a retelling of stories from the Buddha's previous incarnations. Comedy and farcical plotlines are a large part of both types of performance.

But the masks themselves, which form the basis of the colorful puppet faces too, originate from a much darker place in the people's psyche.

Masks from Ambalangoda and other maritime towns were first used thousands of years ago in exorcism rituals, in what was called "devil dancing" or thovil. This tradition of ritual therapeutic theater dates back over 2,500 years to pre-Buddhist times.

A puppet from an ancient folk tale, dramatized (Photo by Rajpal Abeynayake)

A puppet from an ancient folk tale, dramatized (Photo by Rajpal Abeynayake)The puppeteers from Ambalangoda also draw on the nadagam, the South Indian dance drama tradition imported from Tamil Nadu in southern India by colonizing Catholics.

Supun Gamini, a computer science and management graduate, is a fourth-generation puppeteer who has launched a determined effort to keep Ambalangoda's rukada art alive.

His greatest challenge, he said, is to work around some aspects of tradition that he feels deter people, especially the young, who prefer today's internet-generated popular culture instead.

Some of the traditions associated with masks and puppetry are dying out, but that may not be an entirely bad thing, according to Gamini. Ignoring some aspects of the ritual may be the way to let the puppet art and masked dances live on.

"For example, each time they cut down a kaduru tree for crafting masks or puppets in the days of my forefathers, they enacted elaborate rituals before the tree was felled," said Gamini. These rites were meant to propitiate the divine beings.

Supun Gamini, a puppeteer, with a puppet styled after the thovil mask tradition (Photo by Rajpal Abeynayake)

Supun Gamini, a puppeteer, with a puppet styled after the thovil mask tradition (Photo by Rajpal Abeynayake)

None of that happens now, said Gamini. The need for this particular tradition seems absent when most of the puppet and kolam tales borrow from ritual for dramatic content anyway. So sacrificing this aspect has not done the art itself any damage, he explained.

Similar forces are shaping Ambalangoda's kolam masked drama. Tukkawadu Harischandra is, like Gamini, a fourth- generation practitioner, with similar modernizing views. He does not mind if the kolam players blaze new trails and borrow today's political themes as plotlines. But there is no need to overdo it, he said, when the old stories, some stretching back thousands of years, still have relevance.

Harischandra, who likens the kolam tradition to Noh and Kabuki in Japan, said his son, who is a harbor pilot officer, will eventually take up the tradition because he, like his siblings, does not want to see it die.

The same impulse drives Gamini. He says rukada is what his forefathers did, and though fellow graduates from his class in one of Sri Lanka's top universities are aiming for upward mobility through their jobs, he would much rather preserve a tradition that began with his grandfather's father.

The puppets in Gamini's puppet museum are almost life-size. The craftsmen of Ambalangoda made puppets much bigger than they are in most countries, with huge bulging eyes, and usually masses of hair.

Masks for puppeteer Tukkawadu Harischandra on display at the Tukkavadu Gunadasa museum in Ambalangoda (Photo by Rajpal Abeynayake)

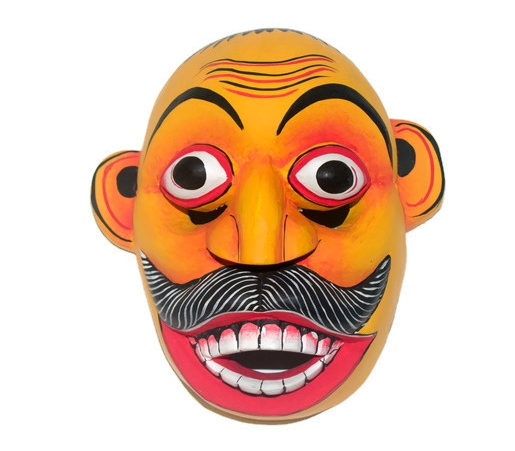

Masks for puppeteer Tukkawadu Harischandra on display at the Tukkavadu Gunadasa museum in Ambalangoda (Photo by Rajpal Abeynayake)The eyes are large on the masks used by dancers in the kolam tradition as well, because the characters were meant to be recognized from far away in large village crowds, said Harischandra.

Whenever Gamini's ancestors performed, the puppeteers often performed skits which evoked the struggles against powerful local royalty, or colonialism.

The Ehelepola saga was once staged by his grandfather's puppet ensemble before the British royals, Gamini said.

This is the story of the bravery of a small child of a hill country nobleman, whose children were put to death by the then Sinhalese king, who had been influenced by the colonizing British. The little prince, Ehelepola Kumaraya, shamed his elder brother, historical lore has it, meeting his executioner with the words: "Big brother, I will show you how to die."

People are intrigued by such explorations of their histories. The tales are told by the lovable-looking rukada and kolam characters. These days most village audiences have not seen them before, because such performances are so rare now.

People are used to seeing the flaws of today's politicians, and both rukada and kolam are a way of indirectly making fun of contemporary personalities. Their lives are reflected in the tales of the past.

The amorous Village Headman portrayed in many of the old colonial era skits could be any modern politico. The Andare or Joker on the Headman's staff, who tricks the master into sharing his mistress, could well be such a politico's bodyguard.

Parody and lampooning are a feature of both art forms, especially the kolam. It is art as a form of pricking pomposities. The puppets and masks themselves make most people laugh, just by looking at them.

In rukada most life-size puppet performances begin with the Jester asking the audience questions. Then the buhubootha dance is pure farce and absurdity. Joker puppets are featured in this slapstick dance form, with an eye on keeping kids entertained.

Kolam in particular uses a fairly rustic brand of humor. In the "Arrachchi Kolama," for instance, the audience awaits the arrival of royalty.

However, it is the head clerk of the Arachchi, or village headman, that appears and is assigned to count the exact number of people present. He adds the unborn babies in mothers' wombs to the head count.

Another tale, "Hewa kolama," is a dig at the colonial powers and was also performed before royalty, among others Britain's Queen Elizabeth II and her retinue, when they visited in 1954.

In the "Hewa kolama," soldiers appear on stage displaying bruises all over their faces. The narrator asks them the cause of their injuries.

They say they had to fight off British troops on the way to the ceremony to welcome British royalty. In fact, they were the King's guards, who were supposed to clean up the streets for the arrival of the visiting royals.

They look at each other bemused and say they jumped into the Kandy lake on the way, and blood-sucking leeches fixed onto the bruises, making the wounds even redder, and more prominent.

At this point they all look at each other and burst out laughing and demand toddy, a local coconut liquor, from the audience before sauntering offstage.

As in Kabuki, the kolam actors are all male, and this includes the actors behind the female masks. These traditions are sacred, and should not be tampered with, said Harischandra.

Kolam originated in ancient times, Harischandra noted. The mythical King Mahasammatha's wife wanted to see some funny and entertaining theater while suffering pregnancy cravings. So the king's courtiers organized a masked theater performance, and the queen's yearnings were satisfied.

In the past, these mythical origins were remembered with the arrival on stage of a character portraying a pregnant queen. But there is nothing sacred about these motifs, and introducing a degree of flexibility toward tradition has been a success for Harischandra, and others like him.

"Badadaru Kathawa" is a kolam story as old as the sea around Ambalangoda.

Its central character is a pregnant woman who appears on stage lamenting her labor pains. The narrator asks her what her problem is, and her reply is that all the men in the audience put her in this condition.

The woman says the men pledged gifts of clothes and jewelry but did not keep their promises. It is a typical trope for an audience accustomed to knockabout, interactive comedy.

After a few twists and turns to the plot, the work is done for Harischandra and his colleagues. The ancient theme of pregnancy has been kept intact, even without the old ritual of the pregnant queen appearing before the performance.

"We are not commercially minded," said Harischandra. "But we know how to draw the crowds anyway."

As his father’s art form diminishes, Tharanga said, his ambition was to preserve the puppetry tradition of the chief pioneer Podi Sirina Gurunnanse. “This is important as the puppetry now is on the verge of disappearing forever”.

As his father’s art form diminishes, Tharanga said, his ambition was to preserve the puppetry tradition of the chief pioneer Podi Sirina Gurunnanse. “This is important as the puppetry now is on the verge of disappearing forever”.

DANCE: The earliest known masks have been found in the excavations of the Harappan civilization of India datable to 3000-5000 B.C. Since then masks have found their way universally to all civilizations. Seemingly masks have had their origin from the inborn desire of man in his primitive days to disguise themselves in their hunt for food.

DANCE: The earliest known masks have been found in the excavations of the Harappan civilization of India datable to 3000-5000 B.C. Since then masks have found their way universally to all civilizations. Seemingly masks have had their origin from the inborn desire of man in his primitive days to disguise themselves in their hunt for food.