Dancing Masks of Sri Lanka

The Yakun Natima – devil dance ritual of Sri Lanka

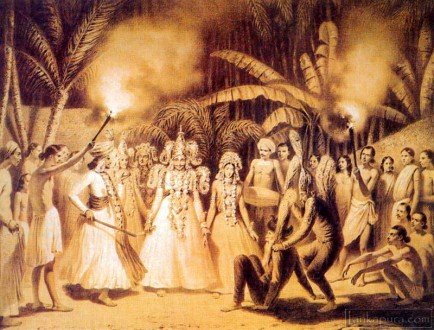

The yakun natima or Traditional devil dance ritual in 1800s in Sri Lanka

Of all the dance rituals, the yakun natima focuses most directly on healing. In Sinhalese thought diseases are either caused by the natural or the supernatural. In the case of the natural, traditional Ayurvedic and/ or medical avenues are pursued. In the case of the supernatural, or where the other systems fail, they have traditionally turned to the edura for aid through such rituals as the yakun natima.

In both cases, however, it is the cause rather than the symptom that must be addressed. And in the case of the supernatural it is the yakku demons that are the cause (6). Collectively, these disease-afflicting demons are known as the sanni yakku. They are a group of demons who, in past battles with the Buddha, were ultimately banished from earth. Living under the loose control of their king Vesamuni (from which the term for mask, vesmuna, is derived), the yakku are unable to appear physically upon the earth, but retain the power to afflict, and through the influence of the Buddha, to heal.

The Eighteen Sanni Yakku

Every demon has an identity, a story. Unlike among the Balinese, where demons often represent types (i.e., hero, villain, clown, etc.), the Sinhalese yakku represent individual demons whose lineages and exploits are recited and commemorated. The masks used in the various rituals are carved to represent particular demons and can, with some exceptions, be specifically identified. Although the yakku. seem limitless in number, there is a core group of eighteen which form the focus for the yakun natima rituals.

Known as the daha-ata sanni yakka, these demons represent specific afflictions, both mental and physical, which commonly afflict the Sinhalese villagers. Although the number eighteen has now become standard, indications are that this number has decreased over time. Nor are the identities of the eighteen consistent. Different areas, or even different communities within the same area, will count different demons among the list.

Paul Wirz, in his seminal work Exorcism and the Art of Healing in Ceylon (1954), lists the following demons and their effects: Kana-sanniya (blindness), Kora-sanniya (lameness/paralysis), Gini-jala-sanniya (malaria), Vedda-sanniya (bubonic plague), Demala-sanniya (bad dreams), Kapala-sanniya (insanity), Golu-sanniya (dumbness/muteness), Biri-sanniya (deafness). Maru-sanniya (delirium). Amuku sanniya (vomiting), Gulma-sanniya (parasitic worms), Deva-sanniya (epidemic disease, i.e. typhoid, cholera), Naga-sanniya (evil dreams particularly with snakes) (7), Murta-sanniya (swooning, loss of consciousness), Kala-sanniya (black death), Pita-sanniya (disease related to bile) (8), Vata-sanniya (shaking and burning of limbs), and Slesma-sanniya (secretions, epilepsy).

Surveys by individuals such as Alain Loviconi and E.D.W. Jayewardene, have demonstrated significant differences between various areas and the impossibility of creating a universally recognised list. One area might include 0lmada sanniya (babbling) and another area Avulun sanniya (breathing difficulties, chest pains). Contemporary ethnographers such as Obeyesekere have also noted the addition of certain more contemporary maladies to the list. For example Vedi sanniya as relating to gunshot wounds, dramatically reflecting the change in times and the adaptability of this indigenous system.

Although there is no single, uniform list or all eighteen demons, certain demons do seem consistent and universal, such as Biri for deafness, Kana for blindness (9), and Golu for dumbness.

Presiding over these eighteen yakku is the demon known as the Kola sanni yakka (10), a composite demon containing and regulating the other eighteen. In the yakun natima it is appeasing the Kola and gaining his benediction that is most important. His origin story, as recorded by Wirz, is as follows:

A certain king left for a great war, leaving behind his queen. He was unaware that she was pregnant. Upon his return he found his wife to be in an advanced state and ready to give birth. A handmaid to the queen, through lies and deceptions, convinced the king that it was not his child but that of the war minister, who had remained behind. In a fury he ordered the queen tied to a tree and cut in two. The child managed to survive, living off the remains of his mother. As he grew, the child vowed revenge on the father.

He gathered poisons from the different parts of the forest and formed them into eighteen separate lumps which transformed into demons. Kola sent these demons into the city and charged them to “capture humans and cause illness through wind, phlegm, and bile”.

The havoc wreaked on the city was awesome. Buddha, sensing this, came to the city and, appearing overhead, ordered Kola and his demons to stop. Angered, Kola attempted to refute the Buddha, vehemently justifying his actions based on the grievous wrongs done to him. But with a “single glittering ray” Buddha subdued Kola and ordered his chiefs to use water to cleanse the city and wash away the demons. Kola persisted in trying to justify his actions and the Buddha ultimately relented, granting Kola and his demons the power to afflict, but charging that they must also heal these afflictions when tribute is paid.

Identities

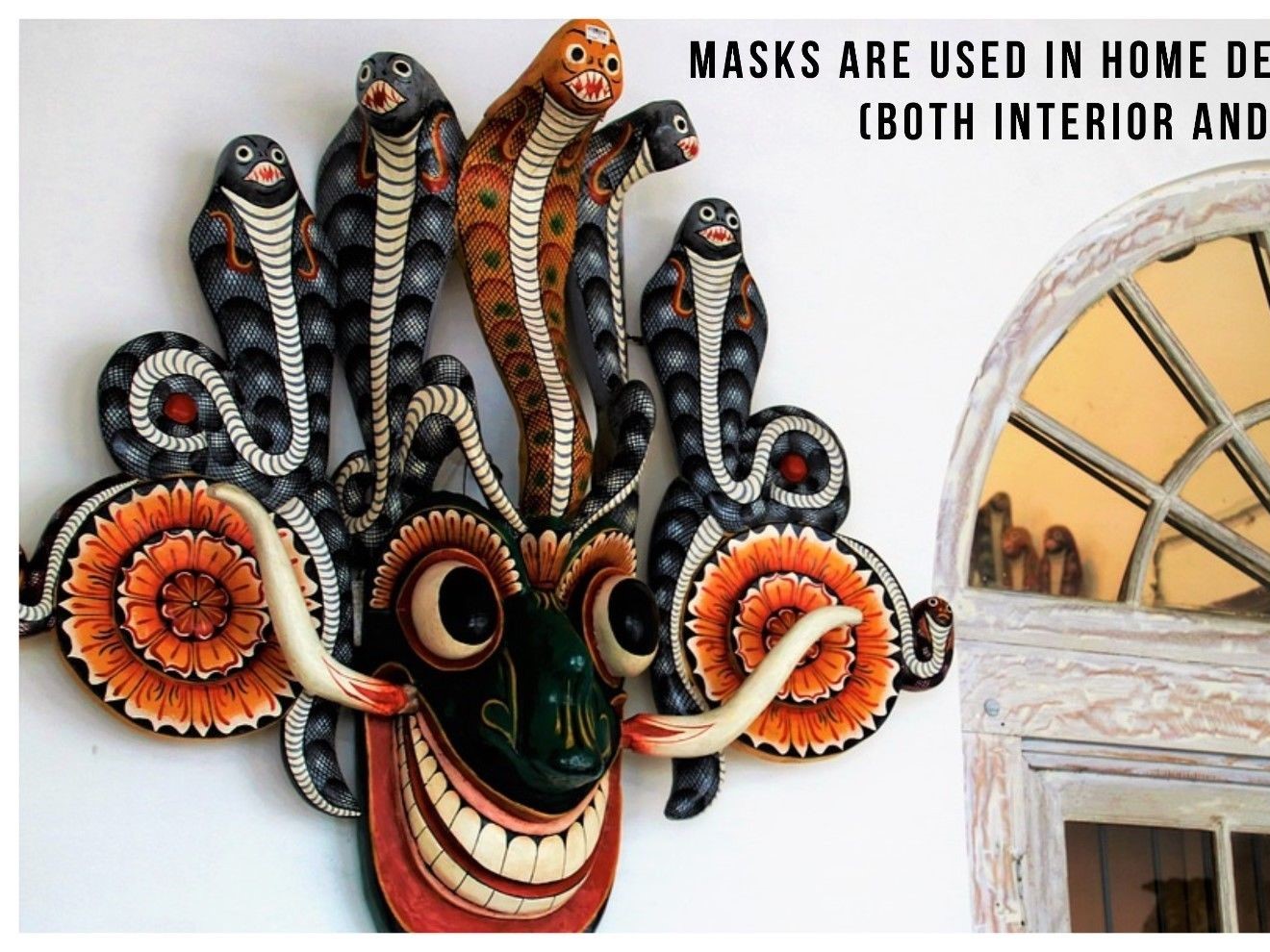

Accounts and photographs of masked dancers with bulging eyes, tusks, and gaping mouths have long attracted ethnographers and the curious. The result is that European museums boast significant collections of wondrous masks carved of wood with exquisite artistry, depicting a phantasm of creatures. The masks of the yakun natima, befitting their function, are generally gruesome, with distorted faces, cobras (called naga) coiled like crowns atop their heads, eyes bulging and strong protruding noses with flaring nostrils. They are powerful carvings designed to inspire fear, awe, and a recognition of the presence of these supernatural beings in our daily lives.

Although the identities of some demons are difficult to ascertain out of context, many masks can be readily identified by form and colour. Biri-sanniya, the demon for deafness, for example, is consistently depicted with a cobra emerging from one eye and covering the side of the face where the ear would be. This relates directly to the Sinhalese belief that the cobra has no ears and therefore must “hear” with its eyes. Kora sanniya, the demon for lameness/paralysis, is often depicted with the features of one side of the face drawn up, approximating the signs of a stroke (11). Amuku sanniya, the demon for stomach disorders and vomiting, is often depicted with a green face, wide open eyes, and a partially protruding tongue (12).

The yakun natima and other masked dances of the Sinhalese are all based on the concept of appeasement. They acknowledge the influence and power of the yakka as both the cause and the cure. They recite their histories, extol their power, and pay tribute to their prowess. These ceremonies are designed to call forth the “essence” of the offending demon. Through sweet-talk and offerings or through cajoling and threats, the yakka is made to remove the affliction.

Kolam Natima

The kolam natima belongs to a different category of ritualised mask dance than the yakun natima. Today it is rarely practised and has been gradually losing its importance over the last hundred years. The early twentieth century writer Otaker Pertold commented that, even in his day, much of the original import of the dance had been lost, and that on the few occasions that it was still performed it was undertaken by laymen rather than edura or those specifically versed in ritual dances. Because some forty masked characters are involved in this elaborate drama, with commensurate offerings expected for certain devils and demons, Pertold cites the great expense involved in staging a full kolam natima as responsible for its gradual abbreviation.

As a ritual, the kolam natima broadly centres around pregnancy issues. The cravings and desires (dola duka) that often accompany a pregnancy were traditionally viewed with great suspicion, and were believed to be some sort of supernatural possession. The masked dance is thought to have been principally directed against these cravings and to protect the fetus in general.

The origin story and characters depicted in the kolam natima reflect some of this original intent:

The queen of a powerful king was pregnant. As her pregnancy neared term she developed an irresistible craving to see a masked dance performed. So intense was her desire that her health rapidly began to fail. ‘She beseeched her husband, the king, to grant her this wish. The king asked his ministers what should be done, but no one knew what a masked dance was. In his desperation the king pleaded to the god Sekkria, asking that he should reveal what must be done. Hearing his plea, Sekkria instructed one of the four guardian gods, the God of Curiosity, to carve masks of sandalwood and place them in the king’s garden with a book detailing what must be done. In the morning the gardener found masks distributed throughout the garden, some with the faces of devils, others of animals, and others of noble courtiers and ladies. The gardener rushed to the king and told him the news. He and the ministers gathered in the courtyard, discovered the explanatory text and a masked dance was performed immediately for the benefit of the queen.

It is assumed that the mask dance did the job, and that she suffered no more dola duka, and that the infant was a healthy one.

Near the final stages of the performance, as translated by Calloway in 1829, a pregnant woman enters the scene and after much anguish gives birth to a son, exclaiming: “The beauty of the child I have now got is like a flower. His prattle will be pleasant, and he will like much to chew betel [nut].” Care is urged for her son, and the demons and devils that threaten it are placated with offerings.

There is very little structure to the dance itself. Following a brief introduction and a retelling of its origins, the ritual consists primarily of a series of dances and walkthroughs by a set of characters; gods, humans, animals, and devils, each successive character being only loosely connected with what preceded. From the introduction at the court, we move out through the village catching glimpses of village life before moving into the woods, where the threats and ferocity of the animals give way to the terror of devils and demons.

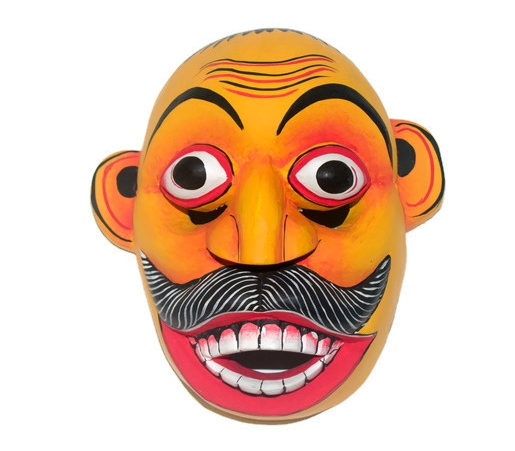

Thus the impact of the kolam natima lies not in its great narrative strength but in the pure spectacle of the masks: the Lasquarine soldier who lost his nose in the great battle of Gampelle; the great Virgin of the Snakes with her radiant face surrounded by coiled cobras; the golden faced and seductive woman with five bodies (13); the greedy moneylender, Hettiya (14); the haggard old man (15) and old woman (16) dressed in rags looking for support from the young villagers; the innocent bullock attacked by a ferocious tiger and a pack of hungry jackals; cavorting monkeys with shaggy beards and gaping mouths (17); the awesome devil Nanda Gere with two devil faces on each side, with gnashing teeth and a body caught in his jaws (18), and Yamma Raksaya, the black-faced devil of death with his long tusks, demon faces flanking his own and coiled naga serpents crowning his head (19).

Construction

Although a brisk trade in masks for tourists has developed in the Ambalangoda area of coastal Sri Lanka, the masks used in the various natima ceremonies were traditionally carved by the edura himself, infusing them with a particular power for the upcoming ceremony. While the edura in his normal walk of life might be a fisherman or farmer, rather than coming from an artisan class, the masks themselves often exhibit a great deal of skill and dexterity in their carving. This reflects the long apprenticeship period that has traditionally been required of all edura, studying under an established figure that may often be the father, uncle, or an elder family member.

Although some of the masks are quite large and complex in their structure, most of those traditionally used in the various natima ceremonies are considered threequarter masks. Strapped to the face, they extend from the middle of the forehead to just below the mouth. This type of lightweight construction makes it easier for the dancer to wear during the often spastic and exaggerated movements executed during a performance which could last up to twelve hours.

Three types of wood are listed as common to mask construction that could vaty depending upon the region and the immediate availability of materials; kaddra (strychnox mux vomica) was prized for its durability (20); eramadu (erythrina india and rukatiana (alsronia scholaris), the latter being considered inferior and known for breaking easily. Divided into blocks, the mask is gradually shaped from the wood. Once the final form is created, the wood is polished using leaves from the mota daliya boodadiya, or korosa trees. Prior to pain g, the polished wood is treated with a t(, clay sealant called allidyu that acts as a gesso and creates a better bonding surface for the pigments to follow.

Although contemporary masks are often painted with commercial pigments, even some of the older masks when they have been repainted reflect this growing trend (21), traditional techniques involve the exclusive use of natural organic and mineral-based pigments. White was derived from makulu clay, green from the leaves of the kikirindiya plant, the ranavara tree, or the ma creeper, blue from the ripe fruit of thebovitiya (22), and yellow from hiriyal orpi ment), or yellow pepper. Black was obtained from charred cotton, and red from cinnabar or a red clay called gurru gal. To protect these pigments the edura would then coat the mask with a lacquer sealant called valicci which was derived from a combination of resins from the hal and dorano trees with beeswax. Hair and beards were simulated through the use of various dyed fibres, elephant hairs, and monkey skins applied directly to the mask.

Nineteenth century and earlier examples preserved in collections retain an amazing vibrancy of colour. An exceptional kolam natima mask of the demon Naga Raksaya was exhibited in the Universal Exposition of 1900 in Paris and is shown here (23). Collected during the middle of the nineteenth century, it is a marvellous example of the strength and durability of the natural pigments used, as well as illustrative of the extraordinary carving talents of the edura

Carved from a single piece of wood with only the small central naga and two ear pendants added, this mask reflects a master ful handling of materials. The painting itself is quite sophisticated with a banding pattern criss-crossing the nose, outlining the mouth and accentuating the eyes. The cinnabar red used for the face glistens through its lacquer sealant. The underbelly of the large central naga, as it executes a graceful arc over the face, is banded and appears very reptilian, as does the crown of three naga on his brow and the coiled naga pend-ants which serve as ears.

The masks of the yakun natima and other dance rituals of Sri Lanka represent a re-pository of a fast-fading culture. Sharing their heritage with a broad range of shaman- based mask cultures of Asia, these masks speak a language which is increasingly fall ing on deaf ears. As the role of the edura becomes increasingly marginalised in Sinhalese society, and education begins to transform traditional concepts of the interaction between the natural and the super-natural, the yakku and the various devils are gradually fading from popular con-sciousness. And while mask carving for tourists and dance performances for the outsider will persist, the fundamental spirit, potency, and vitality of both natima rituals and their masks will sadly be lost. It will therefore be primarily through the older examples, preserved in public and private collections, that future generations will able to recognise the force and the beauty of the devil dance masks of Sri Lanka.