Behind the Mask

Juliet Coombe looks at why masks have long held a fascination for mankind, used both for fun and mystery but also to cover up heinous deeds and, metaphorically, to use as a disguise for more sinister intentions

Many of us first wore masks at school for a play or festival, and later in life perhaps at a masked party or ball, where, suddenly you are confronted by your voice recognition skills and awkward conversations, but masks can also allow people to open up in a way they might feel too timid to otherwise.

Casual observers

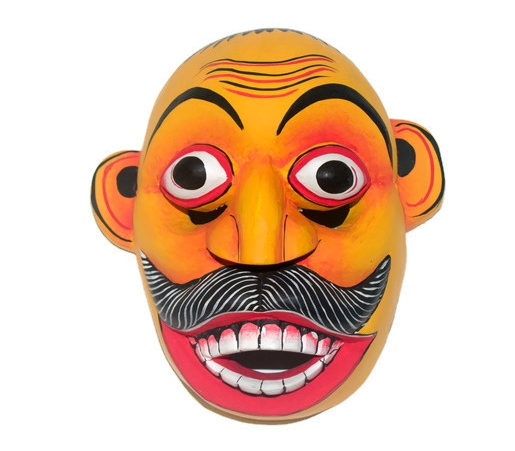

And so it is the case with the Kolam masks, originally developing from the south but later spreading all over Sri Lanka as part of dancing entertainment going back to colonial times, where one way to deal with the sometimes oppressive and strange behaviours of the colonial peoples, was to make fun of, in a subtle and nuanced way, their foibles through plays and dancing – a humorous tonic after a hard week of work on the plantation or whatever other industry might be being exploited. Often such masks would have bulging eyes, terrible stares and weird smiles that helped satirise the objects of their frustration in those days, much in the same way that Spitting Image puppets produced in Britain satirised politicians not so many years ago for precisely the same purpose – to make more bearable the frustrating behaviours of people in power with fixed and eccentric views that made no sense to the average person. It is sad however to think that this art form was designed to highlight a fundamental difference between colonial and indigenous village attitudes towards other people – the latter recognised the value of all persons and how they served the community in an equal way while the former accentuated a hierarchy clearly based on status and the value of different jobs that unfortunately seems to pervade the world today, causing large swathes of the population to feel undervalued and unappreciated.

The masks are normally upon near full-size puppets that are made to dance on strings as well as convey a sophisticated array of emotions. There might be as many as ten puppeteers in a show or drama playing traditional musical instruments, singing and giving speeches. Perhaps, the most notable of puppeteers was Gurunnanse who produced many plays and who, at the peak of his career, performed before the Duke of Edinburgh, Queen Victoria’s son, when he visited Ceylon in the late 19th century and who gave Gurannanse a gold medal and cash prize of five hundred rupees, which was a great deal of money in those days.

Wonderful creations

The third type of mask made in Sri Lanka, the Sanni, is a generally a more disfigured and strange creation that is used mainly for healings and exorcism rituals. So, both mind and body are served by this mask in rituals designed to heal anything from insanity, disturbed sleep through to digestive disorders. There are 18 such masks defined for each type of illness and again they represent a battle against the bad spirits that bring about such illnesses and are used in conjunction with relevant dancing and chanting to bring about a cure, in much the same way that prayer is believed to bring healing to the sick in other cultures and religions.

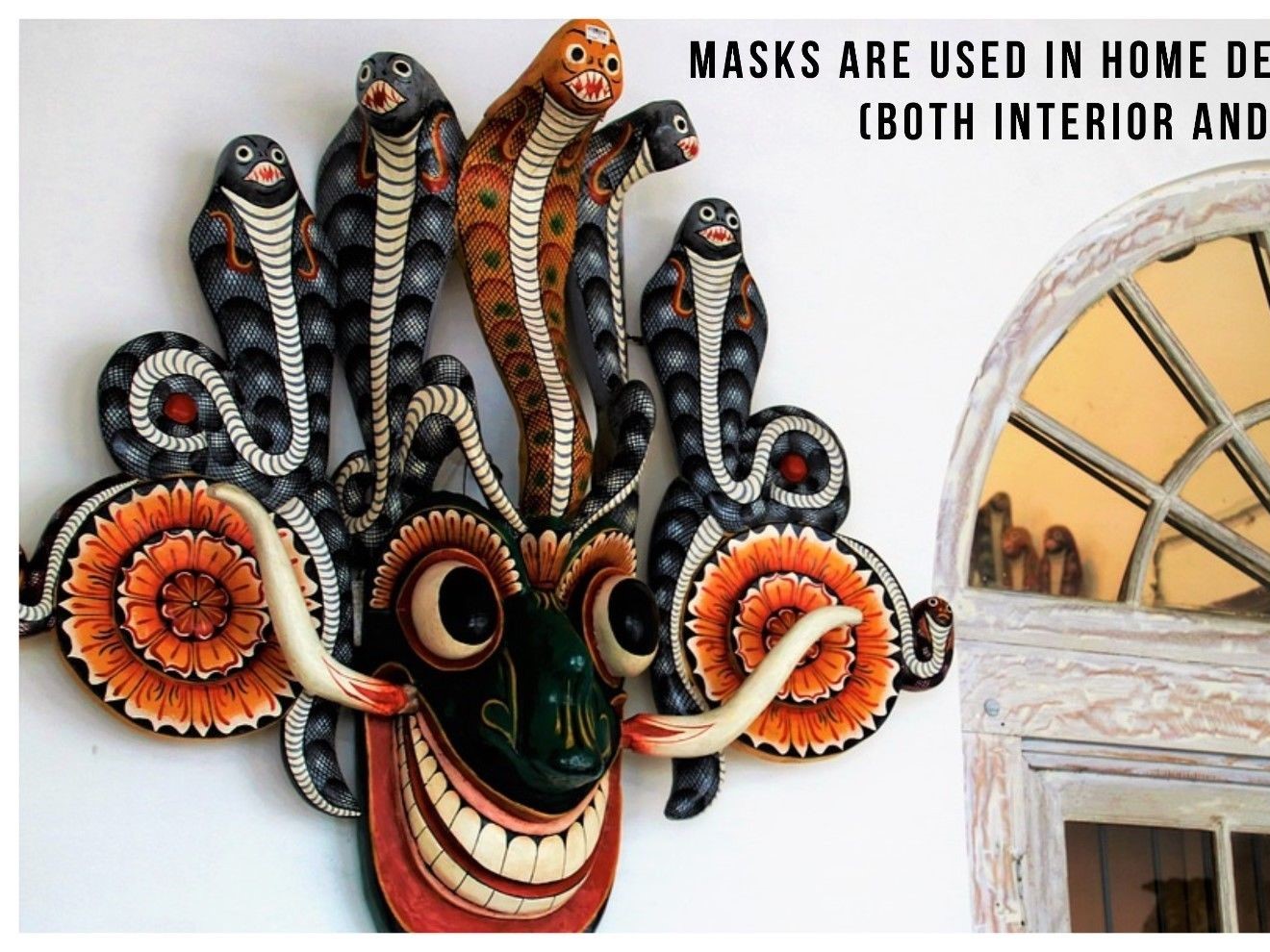

The masks are made all over the island but the greatest concentration of production and skills is around Ambalangoda where they are carved out of a kind of balsa wood called kaduru, which has been smoked for a week before crafting – the wood is still not fully dry when the craftsman takes it up as it can only be carved in a slightly moist and soft state. A mallet and various sized chisels are used, starting with the largest first and going smaller as the mask increasingly resembles the finished product and needs only finer chiselling. The masks are carved according to ancient and prescriptive writings, which have been handed down through many generations and in the case of the other types of masks, the Sanni and the Raksha, many centuries ago, probably dating back to the time of the Buddha.

There are only a few families left who have the real knowledge and skills necessary to produce these wonderful creations but there is a sense that demand may rise with the new wave of tourism that has thrived since the end of the Civil War along with a renewed interest in the mysteries of Sri Lanka, a country that is both one of the most highly educated and advanced in many fields of engineering and science while also being steeped in a tradition of witchcraft considered second only to Haiti in the world.