Kolam Dancing

Kola, Kolam in Tamil means adornment, shapeliness colour, embellicolourt, ornament. ‘Kolum tulal’ is a special temple dance in Kerala. The Tamil words and meaning convey 2 ideas viz: – disguise or dance. The original Kolam story was in Tamil according to the historical Manuscripts, which mentions “usiratanan” and “kalingun rajuge” from the historical evidence available it would seem that the Sinhalese have borrowed this form of entertainment from South India during the Early Portuguese time. This is a masked dramatic performance restricted to the rural areas. It is an open-air show. The audience sits around a screen like the structure of cadjan created for actors to go in and out. At the entrance are two drummers, a Horana player and a couple of singers. The master of ceremonies reads the texts.

It may be possible that there was a form of entertainment resembling Kolam during the medieval Sinhalese time. The Sinhalese did not approve dancing. In the Devales Tamil girls performed the temple dancing. But the earlier records mentioned that Sinhalese as a nation like the ancient Romans seemed to have looked down upon the profession of the dancers and actor. Dancing was performed as a religious ceremony in the Devales. But the dancers were not of the Sinhalese race.

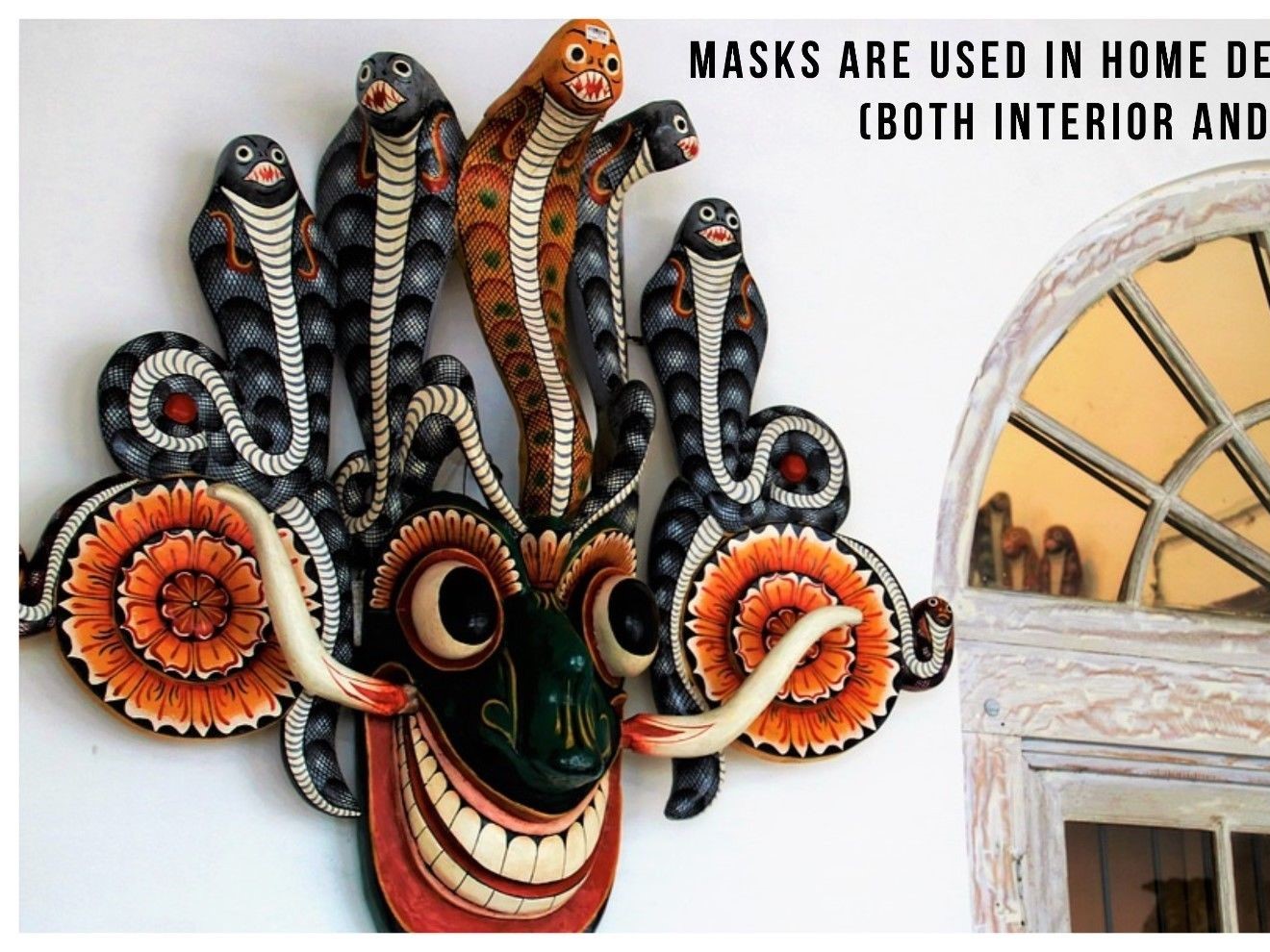

Although the Sinhalese looked upon the dancing and acting as an ignoble art the masses found Kolam a most popular form of entertainment. Kolam flourished in the southern province and the main centres were at Bentota and Ambalangoda. Later it spread throughout low country littoral areas. By the time this form of entertainment became a great deal of borrowing from “tovil” and “bali” had taken place. Even the demon and devil masks were worn. In due course, these two formed a regular feature of Kolam dancing. The handbooks mention them. The description in the texts betrays borrowing from demonological episodes. In some areas, certain characters like karoya karavana rala and Lenchina did not don masks.

As with most forms of art the Indian tradition attributes the origin of Kolam dancing to a sage or original king. Kolam dancing was first performed at the behest of the King Maha Sammata. This was to satisfy the Queen’s longing during pregnancy. The masks were made overnight by Sakra as a present to the king. Some texts mention that Indra was responsible for presenting the masks. Later, a religious bias was introduced by incorporating Buddhist Jataka stories to the existing myths, legends, and other stories.

The earlier stories and legends dealt with demons, devils and nagas. There is a view that Kolam dancing was a pantomime. But this is not quite tenable. There must have been dialogue even as in devil dancing. Without the talking part, much of the burlesque effect would have been lost. The ribald repartee appeared to the audience most. The witty, sometimes obscene exchange of repartee around village characters enhanced the entertainment value. Even in the devil dance the dialogue at times borders on the obscene. This practice may have suggested the necessity to include this type of dialogue from the commencement of Kolam dancing. According to Callaway singing was a modern feature.

The origin of Kolam dancing

There is a view that Kolam dancing originated from an ancient fertility cult of some kind. But most historians believe that it is not the usual fertility cult associated with ancient agriculture societies. One can interpret some scenes as being related to the fertility of women. Two facts seem to support such as view. One is the legend about the origin of Kolam itself, the fulfilment of a longing during pregnancy. The other is the presentation of a scene, where a pregnant woman describes her anxieties, fears and pleasure of childbirth. The present woman herself appears on the stage and expresses the fears and pains of labour. Later the woman returns to the stage with an infant son in arms. She expresses joy at seeing the face of the newborn. Later much didactic material has been added. Buddhist Jataka stories are religiously edifying and the anecdotes from village life are hilariously entertaining. The masks lost their original magic, and religious significance as time progressed. They assumed more and more secular functions in the folk drama, processions and shows.

There are several texts of Kolam dancing. Not all of them agree on the subject matter. Some have more episodes and some less. The British Library copy has 53 characters. The Colombo Museum Ola Manuscripts has the number of verses as in the text printed in 1935. The printed text of Salaman has an added feature. It includes adoration to the Buddha, Dhamma, Sangha and Brahma to bring peace to the patients. The patient mentioned here is the pregnant woman. Then follows of Isvara, Natha, Kataragama, Rama, Kali, Dedimunda and Pattini, other scenes follow. The drama ends with Mahasona and Daka yaka and finally concludes with the blessing.

In another version of Kolam performance ends after episodes of wild dancing in a final scene where gods appear together with the king, queen and ministers and pronounce on the people. According to Raghavan proper Kolam should begin in the presence of the king and queen and thereafter the mythological scenes, demon characters, Jataka scenes etc, should follow.

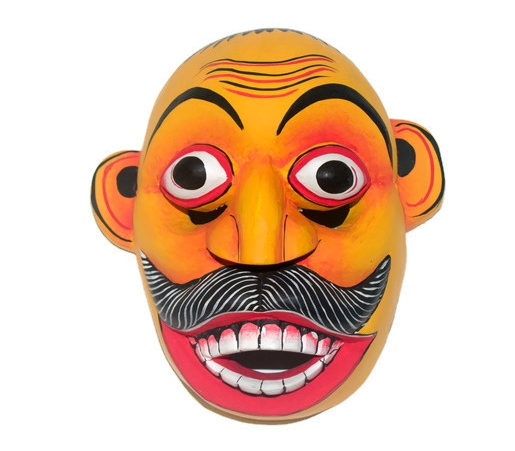

Entertainment and amusement are the highlights of a Kolam dance performance. The actors wear masks without exception. The dresses worn by them suit the rank, position and class of each character in their normal life in society. Village life in all its variety and true character is portrayed. The language used in the dialogue is simple, forceful and striking. The village anecdotes remain unforgettable. The dialogue is impromptu. The allusion and insinuations to local events and characters, though delicate and almost bordering on obscenity, form a part of the fare to be expected.

Kolam dancing was more popular with village folk than any other dramatic performance of a later period. The characterization and expression of moods and ways of life are depicted with skill. Emotions and actions are conveyed as natural and real. Weaknesses of certain characters are well brought out. Typical life in the village is described in words and actions to convey real feelings. Physical characteristic is to be seen in the masks. Old person’s faces appear quite real with fallen teeth, wrinkled skin on face and forehead. The fearsome and the awful; the innocent and the simple; the witty and the gay are some of the feelings enhanced in their appeal by the spicy conversation. In this respect, Sinhala masks resemble those used in Japanese No dancing. The faces of the king and queen are charming and suave with dignity and majesty. “Exaggeration is employed to stress the tragic and comic aspects. The beauty lies in the conventional patterns which are an ancient and very seldom. Many have high merit as sculpture as Hindu art”.

James Callaway has remarked that amusement is the ostensible object and the Sinhalese take much delight in them, the indelible impressions of the most degrading forms are produced in the youthful minds. The entertainment value of the mask is undoubtedly present in Kolam dancing. But the subject matter has developed by the addition of more episodes from the Jataka tales. In the earlier plays, the episodes were limited to Sankapala, Bimsara and Pinguttara. Later gam-kolama, hewa kolama, andabera kolama, maname kolama and sandakinduru kolama etc were added.