- Details

- Written by Manoj

- Category: General

- Hits: 4255

Masks in dance

Mask dances could be divided into three major categories: classical mask dance, folk mask dance and ritual mask dance. Mask dance in classical dances are rare compared to the mask dance found in ritual and folk mask dance. In some classical mask dance items the masks cover the face fully. Some are side face covered masks like those found in Kathakali, the classical dance of Kerala.

Most of these dances use the craft work kreedam (crown). In Bharatha Natyam, a branch which developed in the 20th century, was

|

|

A Therukoothu dance performance |

called dance drama . Different types of masks are used in dance drama according to the needs of the selective characters of the diverse themes. These characters use fully covered face masks.

These masks are mostly made out of certain soft wood which is easy to carve according to the craftsman’s needs. Even dancers in productions like Ramayana use masks which cover the face fully for certain characters like Hanuman, Sukreevan, and Vaali.

Mask making is an excellent and unique talent. It is a good craftsmanship. Many of the families took this profession as family heredity. Unfortunately, such craftsmen do not get much recognition in the modern society. While making the masks the mask maker must express the real facial expressions of the selective characters clearly.

Classical mask dances, and folk mask dances have certain norms. Both provide equal opportunity for creativity within the limited frame work. All the classical and folk dances have certain defined clarified items. The items of the classical mask dances and Folk mask dances have their own defined order. They use certain selected ornaments, and designed costumes. Simillarly each and every Classical and Folk mask dance is based on certain selective music.

Some are accompanied with vocal music alone while some are only accompanied with instrumental music alone.Others are accompanied with vocal music and instrumental music together. Hence all the classical and folk mask dances have a rich, historical background, and longstanding historical developments. Some of the folk mask dances are practised only for certain festivals, and for certain occasions, by a certain caste or clan annually.

Before the introduction of cinema, drama was quite popular among the common masses for entertainment purposes. In Tamil folklore, Naadukoothu , and Therukoothu were quite popular. Both these Koothu forms used masks to depict the characters. Due to the arrival of cinema, teledramas, TV, and home vedio systems, these traditional art forms lost their values and demands. Many of the hereditary actors abandoned these professions, and switched on to other professions. Terrorism in Sri Lanka for the past three decades is also one of the major causes for the downfall of these folk based mask dances.

One of the most popular mask dances of Southern Sri Lanka is Kolam . Different characters are involved in this dance, and beautiful carved masks are used according to the needs of the story. Kolam was originally considered a mask dance form for amusement, but it has a divine origin. Ritual mask dances are also naturally found in Sri Lanka. Generally these ritual mask dances are used for religious,

magical and ritual purposes. This particular variety of dance takes place in open spaces.

Another important mask dance of South Sri Lanka is Sanni Yakuma .There are altogether 18 Sanni Yakuma demons to cure eighteen types of diseases. Each Sanni demon has a particular name and each demon is suppose to heal certain ailments.The dancers represent these demons by wearing specific masks, black coloured costumes and the skirts decorated with leaves.

In West Bengal there are two popular mask dances practised during the Sun festival. Chhau is a ritual dance, and it is also a group dance. Gamphira is another Bengali mask dance but it is essentially a solo dance item.

Mask dance is popular around the world like other dance forms. They are based on their own traditions, and cultural backgrounds

- Details

- Written by Manoj

- Category: General

- Hits: 3627

The craftsmen of Henegama mainly use the timber of the Kaduru tree (Strychnos nux-vomica), which is transported all the way from Elpitiya. It is their choice of wood because the kaduru timber does not rot and is easy to cut. Ruk attana (Alstonia scholaris) timber is also used at times, yet is not the preferred choice. The logs of timber are first chopped into a certain category of size. Then with the porawa (axe) the preliminary shaping of the log takes place.

Next is the most time consuming part, sculpting and embellishing. With nimble fingers craftsmen breath life into the wood, giving it shape, raksha features and imbuing it with centuries worth of tradition. Once sculpted and sandpapered, his day's work is done. The next stage is to paint the basecoat with a substance made at home with whiting (chalk) powder. Laid along tarmacs or home gardens, in the tropical heat they are left to dry.

The Craftsmen Of Henegama Have Quite Talentedly And Nimbly Adapted Their Designs To Suit Modern Requirements. Their Masks Now Come In Mini Versions For Key Tags And Refrigerator Magnets. Or As Larger-Than-Life Versions For Artistic Displays At Leisure Venues.

In the spirit of coexistence and village comradery, in Henegama there is a systematic differentiation of tasks. While the skilled craftsmen sculpture the wood, the talented painters of the village give these masks their charismatic and animated colour. It was amidst one such artist's shed that we met Deepika Rupesinghe diligently immersed in her world of art. Her workspace was cluttered with masks by craftsmen from across the village. To paint the detailed thin drawings, these artists use a brush they make themselves with cat hair; to them there is no finer brush. Though masks of the past had a glossy shine, today the matte texture is popular.

These Masks May Differ From The More Elaborate Ones Of Ancient Times, Yet They Retain The Bold Hues And Features Of Sri Lanka’s Rich Heritage Of Artistry.

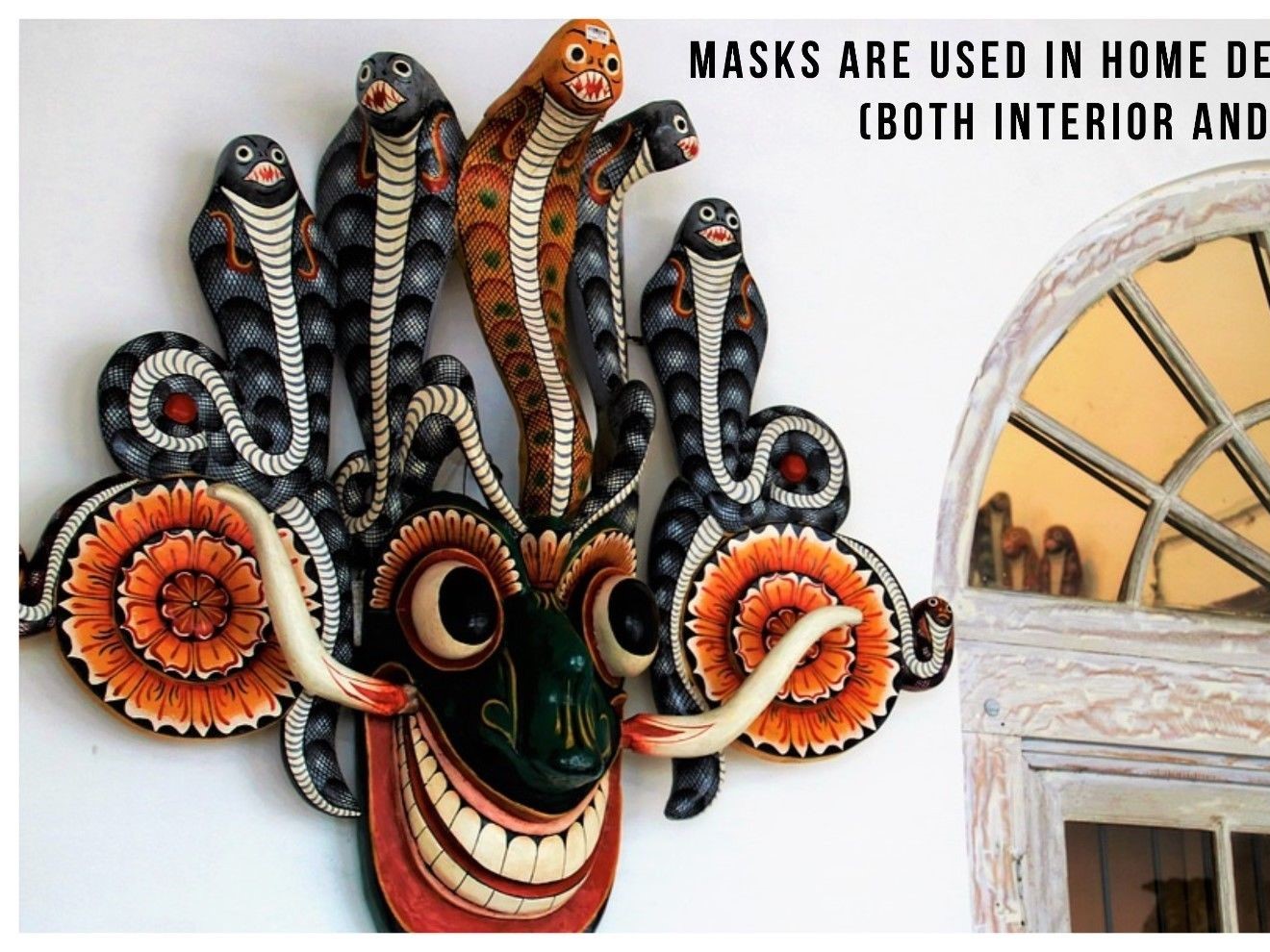

In shape, these masks may differ from the more elaborate ones of ancient times, yet they retain the bold hues and features of Sri Lanka's rich heritage of artistry. A popular mask made in Henegama is ‘Mayura Muhuna' - a mask distinct with blue and green colours and inspired by the peacock. The ‘Ginidel' mask is bright with red and orange tongues of flames. The ‘Ratnakuta Muhuna' is characterised with cobras around it while the Gurulu mask is said to be based on a mythical bird believed to banish cobras.

Designs, with frightful features, are based on the traditional raksha (devil) masks used in raksha folk dances. These were performed for the protection of villages in ancient times, each mask associated with dispelling a particular evil. The masks, of Henegama, though different, are associated with the same apotropaic beliefs. These are sought after for homes and workplaces to be displayed for protection against the evil eye.

Though Henegama cannot trace the origins of mask-making in their village, the decades old tradition continues. Their tireless efforts and skill keeps alive the island's artistic legacy.

- Details

- Written by Manoj

- Category: General

- Hits: 5513

WHAT'S BEHIND A MASK (ARTISTIC VIEWPOINT)

Q: How does one get into the field of this particular art form, ‘illustration’?

A: I moved into the field of illustration and concept art as a profession from a childhood spent doodling and sketching things that caught my interest. As an illustrator and concept artist I have the opportunity to frequently explore design across a wide variety of subjects. Being a young artist with small following on a platform open to the world is a great way to communicate complex topics. Illustration is an enjoyable pastime for me with the added benefit of an audience that may enjoy the product and also provide valuable feedback.

Q: Some artists create with purpose of providing meaning, others to find meaning themselves. How do you use your platform? What do you convey through your artwork?

A: Social media platforms like Instagram offer artists an opportunity to connect directly with a large audience. My illustrations displayed on Instagram are an attempt at directing people’s attention to contradictory notions in culture and aesthetics and bringing them together in an interesting and oftentimes satirical manner. Scattered among these works are highly stylized illustrations of a more playful nature depicting characters and icons of popular culture in vivid colour.

Q: We noticed an interesting pattern in your works of art, particularly the traditional Sri Lankan masks. Could you elaborate on this choice?

A: The series of works that focus on Sri Lankan devil masks throw a powerful traditional icon into the light of a more modern context. The illustrations are aimed at discussing the place traditions, culture, and the artistic styles born of them, have in a world of technology and convenience. A satirical or humorous tone helps get an idea across better as it opens up debate and comments faster. They are also crucial to challenging antiquated idealism or nationalist views by speaking directly to a generation observing, and engaged with, a fast-changing world through social media platforms.

Q: How did you come about the Sri Lankan devil masks and what inspired you to use this as the focus of your artwork?

A: The devil masks are objects with a rich history in the island’s pagan rituals and endemic narratives; they hold a mythical status while being tangible and tie in strongly with early concepts of good and evil, or deities offering protection and fortune. This has been carried forward through generations resulting in a diluted concept of the island’s cultural aesthetic and perhaps even identity. These masks have become ingrained in the social mind as a traditional image that can be used to open an easy portal to a mass market on the international stage. They have become a popular ornament and a declaration of national pride.

- Details

- Written by Manoj

- Category: General

- Hits: 3959

Professor M. H. Goonetilleka - (An academic form of masked dancing)

Professor M. H. Goonetilleka, the undisputed authority on Sri Lanka's masks, is not a man to hog the limelight. In fact the unassuming retiring academic is the most of modest of men. However he was in an angry mood recently. He was driven to both anger and sorrow that a man's lifetime contribution to a chosen discipline could be so easily forgotten or brushed aside.

Writing about a recent book on Sri Lanka's kolam tradition one of Prof. Goonetilleka's own colleagues had swooned over the achievements of that writer who was only bringing out his first book without even a passing reference to Prof. Goonetilleka's own pioneering work in the field.

Not that M. H. Goonetilleka needs any advertising or hosannas sung in his name. His works speak for themselves. His English language book 'Masks and Mask Systems of Sri Lanka' and his Sinhala language book 'Kolam, Sanni saha Ves Muhunu' are arguably the most authoritative on this peculiarly intriguing branch of our folk culture.

He is not only an authority on the masks, mask dances and the folk theatre and healing ceremonies of Sri Lanka but also speaks authoritatively of the religious dramas such as the passion play of Duwa which is an outstanding example of how a major Christian theme has been incorporated into Sinhala folk theatre.

Now retired from the Kelaniya University Prof. Goonetillaka's services are much sought after by both foreign scholars as well as overseas universities, research institutes and museums. He has been recognised by the National Museum of Ethnography of Stockholm as the leading expert to document the large collection of Sri Lankan masks owned by the museum.

It is considered one of the major collections in the world and the expertise needed for classifying these masks is not available in Sweden. The documenting of these masks will be part of a project which will also involve making a film of the tradition of Sri Lankan masked dances as well as the art of mask making which is still alive.

Prof. Goonetilleka will also be contributing two scholarly papers to 'South Asia Folklore' a Routledge publication and 'Manisa, 'a bi-annual research journal published by the Indira Gandhi National Centre for the Arts (IGNCA), New Delhi this year. The title of his essay for the first publication will be 'Daha-ata Sanniya and Sri Lanka Masks."

The book review we have already referred to makes a ritual bow to Prof. Sarachchandra's work in the field. While Sarachchandra's book on Sri Lanka's folk theatre is a pioneering work of research it was M. H. Goonetillake, the modest goate-bearded academic who took over the master's torch. It is time that we learnt to honour prophets in our own country without allowing white men and women to do it first.

Book review

Professor G D Kariyawasam - Masks make the men

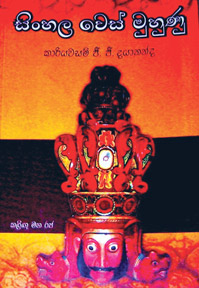

Title: Sinhala Ves Muhunu (Sinhalese Masks)

Author: Kariyawasam G G Dayananda

Publisher: S.Godage and Brothers (Pvt)Ltd)

Pages 128

Mask-making is an art unique to each nation depending on the milieu, time and needs. Mask-making signifies a milestone of human race. In respect of Sinhalese, it stands out as a tremendous achievement, sign of our race and culture in comparison to countries like Burma, Tibet and Bali islands.

Some elite of world fame claim that our masks are attractive and elegant in appearance. They are very popular among the foreigners. But it is very sad to state that today the maskmaking has turned out to be a source of income sans the cultural aspects. They are made as mere selling products to satisfy tourists.

Some elite of world fame claim that our masks are attractive and elegant in appearance. They are very popular among the foreigners. But it is very sad to state that today the maskmaking has turned out to be a source of income sans the cultural aspects. They are made as mere selling products to satisfy tourists.

Historians and scientists who have done in-depth studies into the origin of human art and culture say that possession of age-old masks by any nation testify to the ancientness of that nation. They are of the view that the masks of the old silently speak about the people and belief of a particular time of history of human evolution. The treasured masks we claimed to have in our possession goes to prove that the Sinhala race is one of the oldest among many nations in the world.

The Sinhalese people of the ancient times did believe in heavenly powers, and they implored the intervention of the divine they could not grasp, when they were afflicted by sickness. Gurus, wearing masks, performed a peculiar cult to cure the sick wearing masks and attributing power inconceivable by human mind to the masks.

Sinhala mask-makers supported the belief of the natives that through the devil dancing sicknesses would be cured. Hence there is an indisputable place for mask-making. The book ‘Sinhala Ves Muhunu’ authored by veteran feature writer and journalist, Kariyawasam G G Dayananda, at length explains the roles played by different masks responding to particular needs of each individual affected by evil spirits. The mask is the weapon the demon priest employs to drive the evil spirits. Perusing the pages of this book I recollect a scene from ‘Rekawa’. It opened new vistas to the feature film industry in Sri Lanka and shot Dr. Lester James Peiris to fame. It secured him a place in the international filmdom. The book refers to the scene I recollect in the film (page 74) in two small paragraphs and tries to impress the reader that Rekawa film itself had sanctioned or had confirmed the age old belief that when a kattadiya or yakedura (demon priest) incense the mask of the gara yaka, he is sure to get a visitor seeking his services.

Confirming this age-old belief of the natives, the author refers to that particular scene in his writing about the Sinhala masks, where the boy Sena, the chief character in the film, is sick. His father with a villager, a mudalali who is keen to earn money using the boy’s special power to make predictions, visit the yakedura (demon priest) requesting him to perform the thovilaya, a religious ritual, to cure the boy of all demoniacal possession. Villagers believe that all diseases are supposed to be inflicted by some evil demon in almost all severe sicknesses and the natives heavily depend on the power of the demon priest than upon medicine.

This passage is sufficient to encourage the reader to peruse the pages with keen interest to learn more about this type of rites, rituals and customs and what role the masks play in imparting the knowledge of art and culture unique to our nation. The book contains articles the author had written to local media randomly. Dealing in particular on Sinhala masks, he comes from Ambalangoda, Maha Ambalangoda, of fame both locally and internationally. This village, miles away from the busy city of Colombo, has a name for mask-making.

The book though small in size deals with various topics in 17 chapters and quotes from various authoritative sources including some foreign writers and authors of recognition to underscore the value of our traditional mask-making and what importance the local polity gives to various masks made to suit the different needs and occasions.

The author speaks about the origin, spreading and different types of masks found here and how craftsmen select the wood suitable mask-making, colours used in painting to satisfy those use the masks in performing religious cults to drive away the evils spirits and cure those sick with different ailments.

Prof Tissa Kariyawasam in his preface observes that Sri Lanka had shot to fame with our art of making wesmuhnu used in shanthikarma. He adds that both sanniyakuma and kolam dance originated from the Ruhunu Rata-the Southern Province.

The Christian clergy and the officials who were here during the times of the British period had tried to understand this cult which has a sort of religious flavor but failed to recognize the artistic value of this performing art. They saw in the masks something symbolically fitted against God and Christian religion.

The art of making masks won the attention of the German elite towards the end of the 19th century and of the Czechs in the beginning of the 20th century. The interest they and some of the local elite showed had greater influence on the rest of the locals and pushed them to do serious study on a treasure they had ignored for centuries. Prof. Kariyawasam had expressed his appreciation for writing a book of this nature targeting the ordinary folk.

J Thilakarathne who served in the editorial staff of Daily Mirror as Provincial News Editor, in his remarks, highlights the salient aspects of the mask-making, the author had laboured to convey to the readers.

The book he says fills a vacuum that existed for a considerable length of time, despite the fact that there had been several books written on the subject of Sinhala drama.

The book would be a useful source to those studying Sinhala drama and its history as a performing art.

- Details

- Written by Manoj

- Category: General

- Hits: 4510

Kolam Dancing

Kola, Kolam in Tamil means adornment, shapeliness colour, embellicolourt, ornament. ‘Kolum tulal’ is a special temple dance in Kerala. The Tamil words and meaning convey 2 ideas viz: – disguise or dance. The original Kolam story was in Tamil according to the historical Manuscripts, which mentions “usiratanan” and “kalingun rajuge” from the historical evidence available it would seem that the Sinhalese have borrowed this form of entertainment from South India during the Early Portuguese time. This is a masked dramatic performance restricted to the rural areas. It is an open-air show. The audience sits around a screen like the structure of cadjan created for actors to go in and out. At the entrance are two drummers, a Horana player and a couple of singers. The master of ceremonies reads the texts.

It may be possible that there was a form of entertainment resembling Kolam during the medieval Sinhalese time. The Sinhalese did not approve dancing. In the Devales Tamil girls performed the temple dancing. But the earlier records mentioned that Sinhalese as a nation like the ancient Romans seemed to have looked down upon the profession of the dancers and actor. Dancing was performed as a religious ceremony in the Devales. But the dancers were not of the Sinhalese race.

Although the Sinhalese looked upon the dancing and acting as an ignoble art the masses found Kolam a most popular form of entertainment. Kolam flourished in the southern province and the main centres were at Bentota and Ambalangoda. Later it spread throughout low country littoral areas. By the time this form of entertainment became a great deal of borrowing from “tovil” and “bali” had taken place. Even the demon and devil masks were worn. In due course, these two formed a regular feature of Kolam dancing. The handbooks mention them. The description in the texts betrays borrowing from demonological episodes. In some areas, certain characters like karoya karavana rala and Lenchina did not don masks.

As with most forms of art the Indian tradition attributes the origin of Kolam dancing to a sage or original king. Kolam dancing was first performed at the behest of the King Maha Sammata. This was to satisfy the Queen’s longing during pregnancy. The masks were made overnight by Sakra as a present to the king. Some texts mention that Indra was responsible for presenting the masks. Later, a religious bias was introduced by incorporating Buddhist Jataka stories to the existing myths, legends, and other stories.

The earlier stories and legends dealt with demons, devils and nagas. There is a view that Kolam dancing was a pantomime. But this is not quite tenable. There must have been dialogue even as in devil dancing. Without the talking part, much of the burlesque effect would have been lost. The ribald repartee appeared to the audience most. The witty, sometimes obscene exchange of repartee around village characters enhanced the entertainment value. Even in the devil dance the dialogue at times borders on the obscene. This practice may have suggested the necessity to include this type of dialogue from the commencement of Kolam dancing. According to Callaway singing was a modern feature.

The origin of Kolam dancing

There is a view that Kolam dancing originated from an ancient fertility cult of some kind. But most historians believe that it is not the usual fertility cult associated with ancient agriculture societies. One can interpret some scenes as being related to the fertility of women. Two facts seem to support such as view. One is the legend about the origin of Kolam itself, the fulfilment of a longing during pregnancy. The other is the presentation of a scene, where a pregnant woman describes her anxieties, fears and pleasure of childbirth. The present woman herself appears on the stage and expresses the fears and pains of labour. Later the woman returns to the stage with an infant son in arms. She expresses joy at seeing the face of the newborn. Later much didactic material has been added. Buddhist Jataka stories are religiously edifying and the anecdotes from village life are hilariously entertaining. The masks lost their original magic, and religious significance as time progressed. They assumed more and more secular functions in the folk drama, processions and shows.

There are several texts of Kolam dancing. Not all of them agree on the subject matter. Some have more episodes and some less. The British Library copy has 53 characters. The Colombo Museum Ola Manuscripts has the number of verses as in the text printed in 1935. The printed text of Salaman has an added feature. It includes adoration to the Buddha, Dhamma, Sangha and Brahma to bring peace to the patients. The patient mentioned here is the pregnant woman. Then follows of Isvara, Natha, Kataragama, Rama, Kali, Dedimunda and Pattini, other scenes follow. The drama ends with Mahasona and Daka yaka and finally concludes with the blessing.

In another version of Kolam performance ends after episodes of wild dancing in a final scene where gods appear together with the king, queen and ministers and pronounce on the people. According to Raghavan proper Kolam should begin in the presence of the king and queen and thereafter the mythological scenes, demon characters, Jataka scenes etc, should follow.

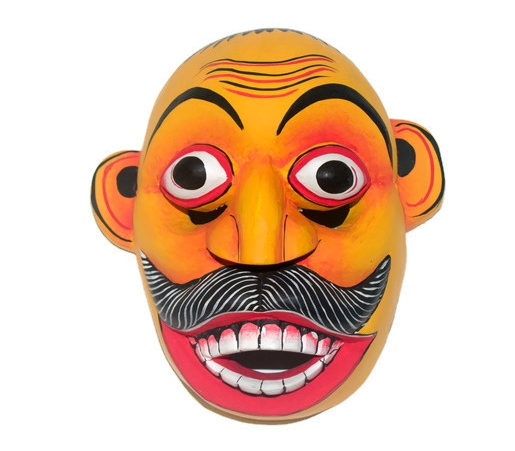

Entertainment and amusement are the highlights of a Kolam dance performance. The actors wear masks without exception. The dresses worn by them suit the rank, position and class of each character in their normal life in society. Village life in all its variety and true character is portrayed. The language used in the dialogue is simple, forceful and striking. The village anecdotes remain unforgettable. The dialogue is impromptu. The allusion and insinuations to local events and characters, though delicate and almost bordering on obscenity, form a part of the fare to be expected.

Kolam dancing was more popular with village folk than any other dramatic performance of a later period. The characterization and expression of moods and ways of life are depicted with skill. Emotions and actions are conveyed as natural and real. Weaknesses of certain characters are well brought out. Typical life in the village is described in words and actions to convey real feelings. Physical characteristic is to be seen in the masks. Old person’s faces appear quite real with fallen teeth, wrinkled skin on face and forehead. The fearsome and the awful; the innocent and the simple; the witty and the gay are some of the feelings enhanced in their appeal by the spicy conversation. In this respect, Sinhala masks resemble those used in Japanese No dancing. The faces of the king and queen are charming and suave with dignity and majesty. “Exaggeration is employed to stress the tragic and comic aspects. The beauty lies in the conventional patterns which are an ancient and very seldom. Many have high merit as sculpture as Hindu art”.

James Callaway has remarked that amusement is the ostensible object and the Sinhalese take much delight in them, the indelible impressions of the most degrading forms are produced in the youthful minds. The entertainment value of the mask is undoubtedly present in Kolam dancing. But the subject matter has developed by the addition of more episodes from the Jataka tales. In the earlier plays, the episodes were limited to Sankapala, Bimsara and Pinguttara. Later gam-kolama, hewa kolama, andabera kolama, maname kolama and sandakinduru kolama etc were added.

Page 3 of 13