“Masks of Sri Lanka Exhibits”

Visitors at the Viewpoint Gallery witness an interesting Illuminations exhibit of masks of varying colors, each intricately detailed and hypnotizing. The masks were arranged by international student Danushi De Silva. The exhibit, titled “Masks of Sri Lanka: Face to Face Communication,” provides a cursory glance at the rich amount of tradition underlying the masks.

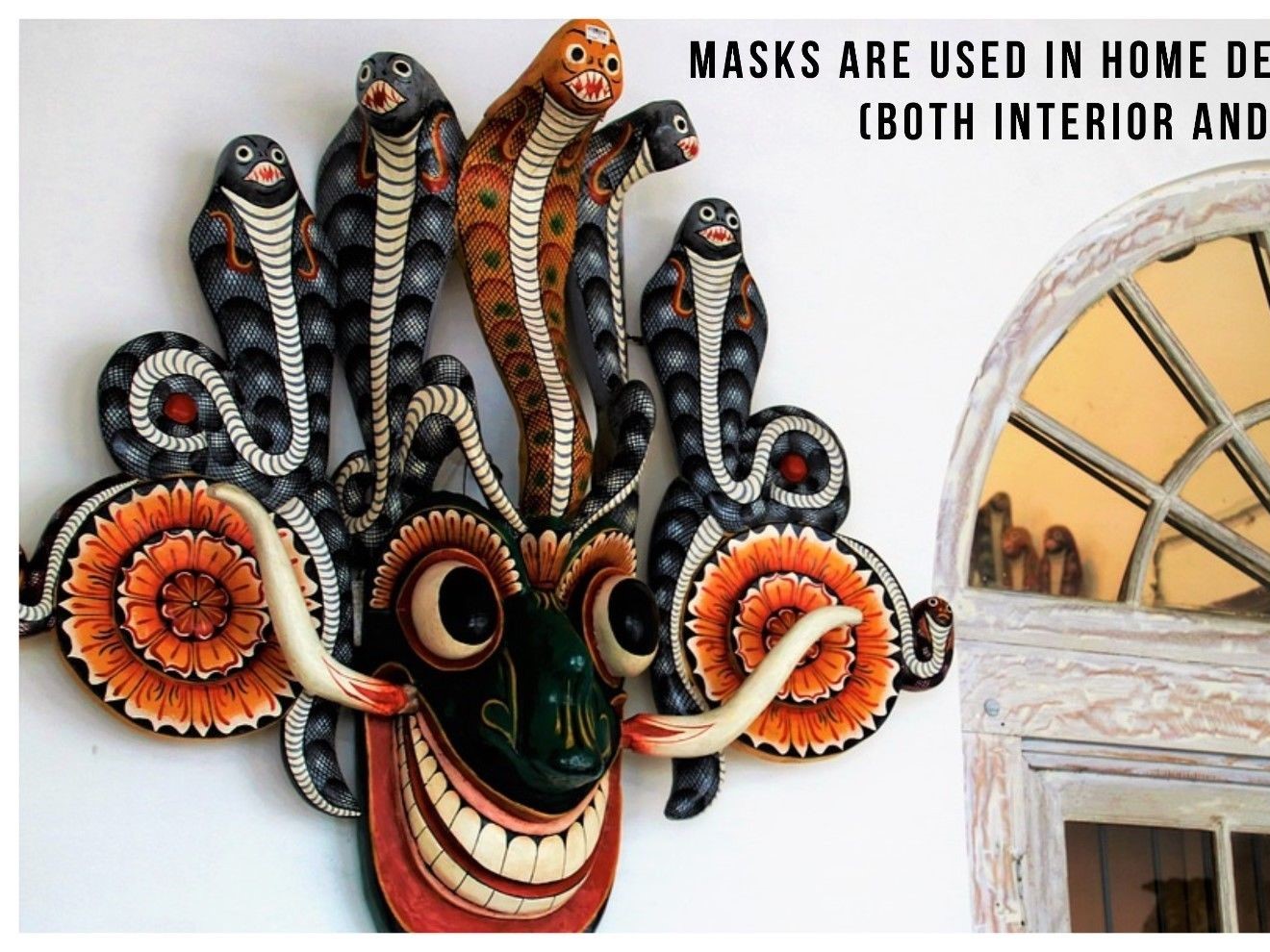

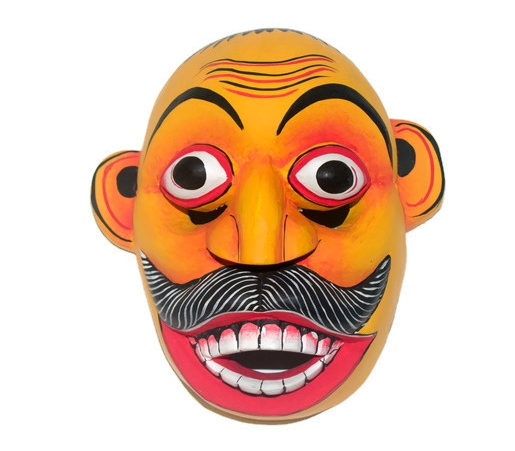

While walking around the exhibit, the amount of detail on the masks is evident. They came in varying forms and were crafted with a high attention to detail. Each one is rendered with lush color. Even through the images the textures popped out and each mask gave off a vibrancy. They possessed deep grooves and hard edges, yet maintained a flowing appearance when viewed from afar. It was not hard to get absorbed in the images themselves and imagine coming face to face with one.

Traditional ritual masks dating back as far back as 2,500 years ago may have been used for entertainment, but that wasn’t their only purpose. Other masks played roles in society such as curing sickness. There were 18 unique masks designed for performance in a ritual to cure illness. According to the Illuminations guide for the exhibit, such masks acted as representations, mirroring the 18 malignant spirits that caused a number of ailments.

European exporting of the masks to museums, where they were paraded as objects of spectacle, reduced their use in the places they came from. De Silva’s photographs capture traditional masks from a range of locations such as the Traditional Puppet Art Museum, the Colombo National Museum, the Ariyapala Museum and a mask festival typically held in Colombo.

Looking at the images, it’s hard to imagine that some of the masks pictured are more than 150 years old because their vibrance and eye-catching characteristics made them look like new. There were a few physical representations present as well in the exhibit that added another dimension of visualizing the traditional masks. Being so close to these was almost taunting as one was compelled to imagine what the masks would look like when actually utilized during a traditional ceremony.

The exhibit as a whole brought a novel perspective to depicting the traditional ritual masks of Sri Lanka, but the inherent issue with images and even physical masks is that the display was incomplete. We, as viewers partaking in the dissemination of the tradition by learning about it, are deprived of the actual experience of seeing the masks as they were originally used. The importance of these masks is not just within the level of detail and care that went into crafting them, but also the faces of those who wore them in illustrative performances. Ultimately, this is a powerful statement, as the masks are no longer being used as they were in the pre-colonial era and now serve as relics of yesterday’s traditions.