Masks of endless style have been worn worldwide since antiquity to provide physical and psychological transformation of character. Sri Lanka has a distinctive mask heritage, and enjoys a living tradition in mask dance-drama: dozens of types of mask, many bizarre, are used in spiritual, secular, magical and even exorcism rituals.

Part the veils of time and legend and you would probably find an island inhabited by several self-described clans, the largest called the Yakkas, ‘demon-worshippers’, another the Nagas, ‘snake-worshippers’, in particular the cobra. More mythical were the Rakshasas, who were shape-changers. These clans, whether they existed or not – and there is reason to believe the first two did – have had a profound impact on the evolution and symbolism of masks in Sri Lanka.

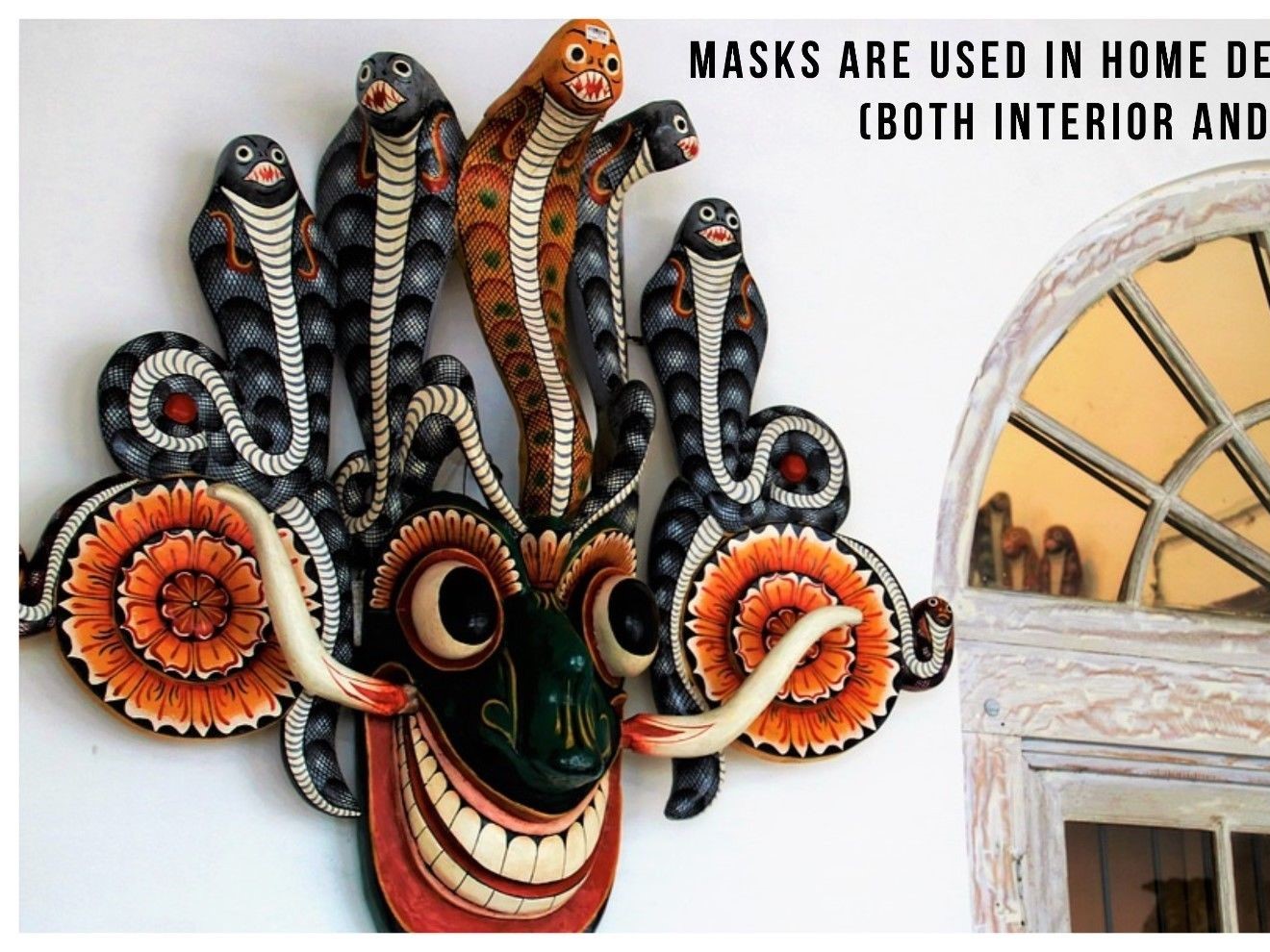

After the ‘disappearance’ of the Yakkas, early travellers visiting the Island related tales of how the inhabitants worshipped demons believed to live in trees. These demons, called yakkas of course, were worshipped in a quest to pacify them, to avert their evil forces, and the participants wore fearsome masks with a devilish face festooned with cobras.

The ancient history of the art of masks in Sri Lanka is inevitably shrouded, although it is believed to have originated in the South Indian state of Kerala, where the raw material used was palm leaves. When the tradition filtered to Sri Lanka and took hold in the South, in particular the coastal town of Ambalangoda, the soft, balsa-like wood of the strychnine tree (Strychnos nux-vomica), known as goda kadura, became the substitute material.

Over the centuries, mask forms evolved for differing mask-drama, yet yakkas often lurked. In the award-winning children’s novel Mythil’s Secret (2009), Prashani Rambukwella explores the belief in yakkas and the influence of masks through the eyes of a young boy, Mythil: “Quite suddenly the fruit seller looked straight at him – with the face of a yakka! He had glowing red eyes and tiny tusks protruding from under his upper lip.”

When Mythil is rescued from two yakka spirits they turn into pale blue ghosts and he realises “the only substantial thing about them were their masks”, in which, he learns, their memories are written, to be reclaimed the next time the spirits manifest themselves...

Masks generally fall into three categories: kolam, sanni and raksha.

Kolam Is A Comic Folk Play – Once Popular Now Rarely Performed – Made Up Of Loosely Connected Stories In A Rural Setting, Enacted Through Dance, Mime And Dialogue

Kolam (Dance-drama masks or the Kolam theatrical masks)

Sri Lanka has a rich culture of masked dance-drama, the best-known form being kolam (Tamil for “costume” or “guise”), which is mainly performed in southern, rural parts of the island. The masks associated with kolam number around 50 and are the most elaborate of the three categories. Faubion Bowers comments in Theatre in the East (1956) that they are “the finest examples of wood-carving still being executed for the theatre in the modern world”.

Kolam masks are used in folk-plays and dramas. In the early 16th century Europeans introduced, Sri Lanka to a form of mask dancing known as Kolam from south India. These masks were used for theatrical purposes and usually had a king’s name to honor it. The performances of these masked dancers were mainly for the royalty and the masks were carved by the carpenters specially retained by the king. These exquisitely made and conserved masks, used for folk theatre, are distinctly different from devil-dancing masks. Characters are divided into humans (royalty, a variety of villagers), animals (bullocks, monkeys) and demons. Such masks depict the faces of kings, queens, princes, ministers, men and animals.

Kolam is a comic folk play – once popular now rarely performed – made up of loosely connected stories in a rural setting, enacted through dance, mime and dialogue. The performances shift from the portrayal of 19th Century village scenes to stories involving spirits and creatures from Hindu mythology.

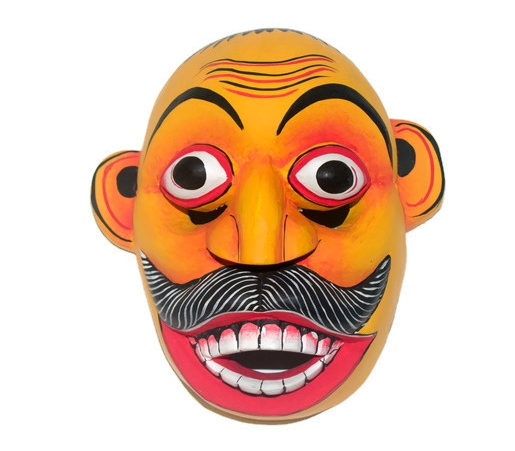

The impact of the kolam lies not in its narrative strength, but in the spectacle of the masks. A typical blend of sculpture and painting, the masks are often grotesque with bulging eyes, though some have humorous features. Notable aspects include the magnificent towering head-pieces of the king and queen, and the lengthy beard and largely toothless appearance of Anabera, the drum messenger. In contrast, the masks of the policeman, the Mudalali (shopkeeper), the Arachchi (village headman), and Hettiya (the foreign trader), are more conventional. As for the demons, there’s the awesome Nanda Gere, with two devil faces on each side, and a body between its teeth.

Thovil and Sanni (ceremonies to exorcize disease –causing demons)

Thovil and Sanni are dance ceremonies to exorcize disease –causing demons. The witch doctors (kattandiyas) impersonate these demons wearing masks and costumes. Some of the masks used in these rituals, like the 18 sannidemons, each have its own, distinct features, symbolizing a particular sanni or disease.

Diseases have traditionally thought to be sometimes caused by yakkas and other evil forces. When it is believed, for example, that a lingering sickness is caused by such forces, the patient’s family used to turn – and still do to a limited extent – to an edura, or exorcist, to perform a tovil, or devil dance, characterised by the wearing of yak vesmuhunu, devil masks. It’s an ancient healing ceremony that treats the cause of the disease not the symptom, a basic tenet of alternative medicine such as Ayurveda.

Demonic participants include the much-feared Maha Sohona “demon of the cemetery”, a giant beheaded in a duel who now possesses a bear’s head, represented by an awesome mask with extended tongue. Maha Sohona is threatened with further humiliation unless he relinquishes his grip on the patient’s health.

Most important are the 18 sanni (“disease”) demons that represent specific physical and psychological ailments visualised in the leering masks. The full complement is rarely represented; only the most likely demons to be causing a person’s affliction are worn. During the exorcism the sanni demons are summoned, offered tribute and requested to leave the patient alone.

Finally, there is the appearance of an exorcist wearing the mask of the chief demon, Maha Kola (“the all encompassing one”), which holds afflicted persons in its mouth and hands and is surrounded by cobras and miniature representations of the 18 sanniyas.

Exorcists are reluctant to dispose of sanni masks fearing they might incur the wrath of the demons. Another belief is that when an exorcism ritual is held in one location, masks in other places begin to vibrate. When not in use, the masks are individually wrapped in red cloth and kept separate.

It is felt that the masks’ visual representation is of significance to modern medicine. In “Sri Lankan sanni masks: an ancient classification of disease” (British Medical Journal, December 21, 2006), authors Dr Mark S Bailey and Prof H Janaka de Silva argue that “the classification of disease used in Sri Lankan sanni masks is still relevant today”.

Stomach diseases that cause vomiting are distinguished from those that produce parasitic worms: Amukku Sanniya, the mask that represents vomiting, has a green complexion and protruding tongue, whereas Gulma Sanniya, which represents parasitic worms, has a pale complexion suggestive of hookworm anaemia.

Conversely, the masks for malaria and high fevers, Gini Jala Sanniya, and for cholera and chills, Jala Sanniya, both have fiery red complexions, although the former “can usually be distinguished by flames across the forehead, reminiscent of the temperature chart from a febrile patient”.

Bihiri Sanniya, the mask for deafness is distinctive as it features a cobra that extends from the nose to envelop one side of the face – tradition has it that snakes are deaf, which is only partly true.

Gedi Sanniya, demon of boils and skin diseases has facial lesions resembling carbuncles; Kora Sanniya, demon of lameness and paralysis has a facial deformity that probably represents a stroke; Pith Sanniya, demon of bilious diseases, has a yellow, jaundice-like complexion.

Knowledge of the intricacy of psychiatric illness is evident in the masks Pissu Sanniya, or temporary insanity, Kapala Sanniya, permanent insanity, Butha Sanniya, related to spirits, and Abutha Sanniya, not related to spirits.

“Hence,” the authors conclude, “the sanni demons do seem to represent disease syndromes, and their masks show clinical features familiar to clinicians today. This classification of disease has considerable merit, especially considering its origin among non-medical practitioners many centuries ago.”

Raksha (Demon Maks)

Raksha Masks originated from the south-eastern coast of Sri Lanka. The brightly coloured wooden masks are used in comical theatrical performances.

Raksha masks, larger than the kolam and sanni types, are mainly used in festivals and processions, often to perform Raksha dances within the kolam. Although there are 24 masks of Rakshasa form, few are used in performances, such as the Maru Raksha (demon of death). Inter-related masks are the Naga Raksha (cobra demon), which has an aptly demonic face with protruding hood-distended cobras, while the Gurulu Raksha (bird demon) is of the mythical hawk-like Garuda, able to banish the cobra demon. The dance is apotropaic, its purpose being to avert the danger that venomous snakes pose to villagers.

Sri Lanka’s mask heritage has played an essential role in the country’s society, both in drama and healing, but the associated supernatural beliefs are now eroding, even though mask-making and special performances for tourists persist. Thus it is crucial that older masks are preserved in public collections, to enable future generations to marvel at their brilliance and meaning.

Raksha Masks, Larger Than The Kolam And Sanni Types, Are Mainly Used In Festivals And Processions, Often To Perform Raksha Dances Within The Kolam